LIFE IS SHOT, ART IS LONG

_publication / exhibition

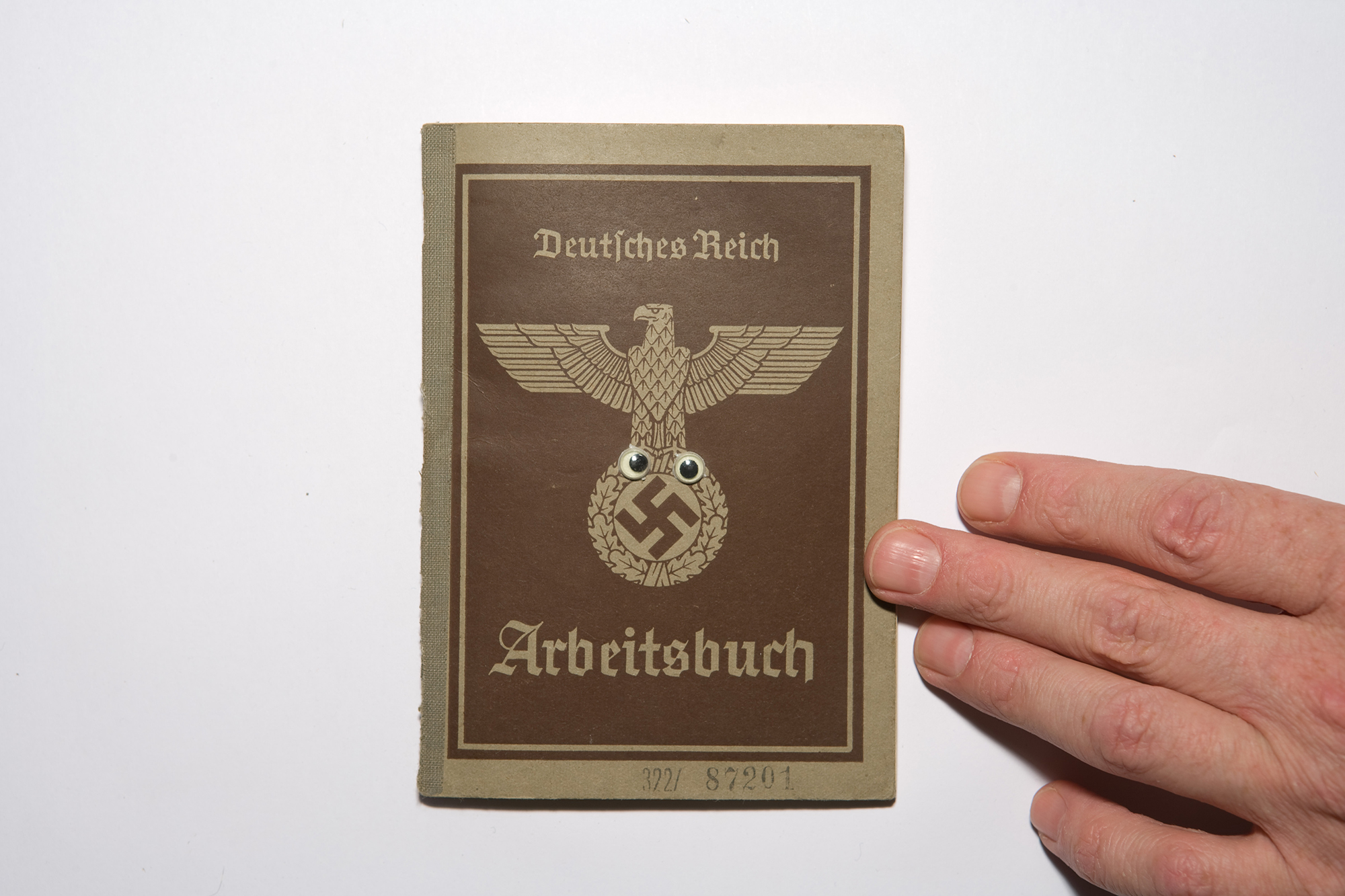

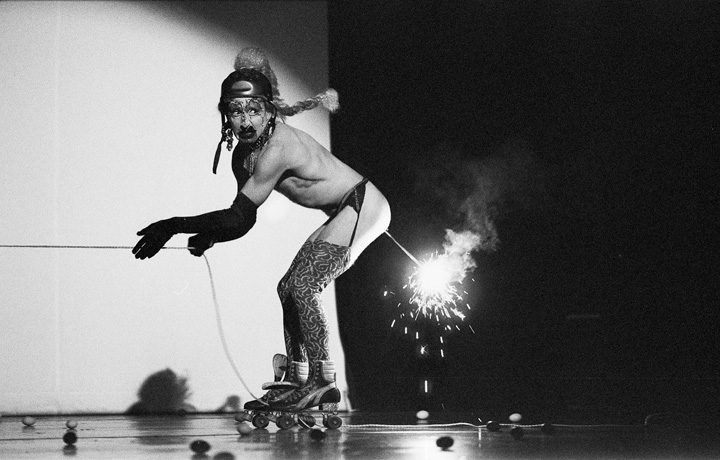

UGLY GIRL (LIVING ART, LUXEMBOURG, MAY 1998)

HAND-COLOURED SILKSCREEN ON CANVAS, BLOOD 91 X 161CM

Life Is Shot, Art Is Long is Steven Cohen’s first solo exhibition in South Africa in over a decade, and the first to take a retrospective view of work spanning 22 years. It is also the first publication devoted to him since the indispensable Taxi-008 of 2003. It represents both a return – to the country of birth and to the gallery context – and a bold assertion of Cohen’s stature as a visual artist.

EXTRACT

A CONVERSATION WITH STEVEN COHEN

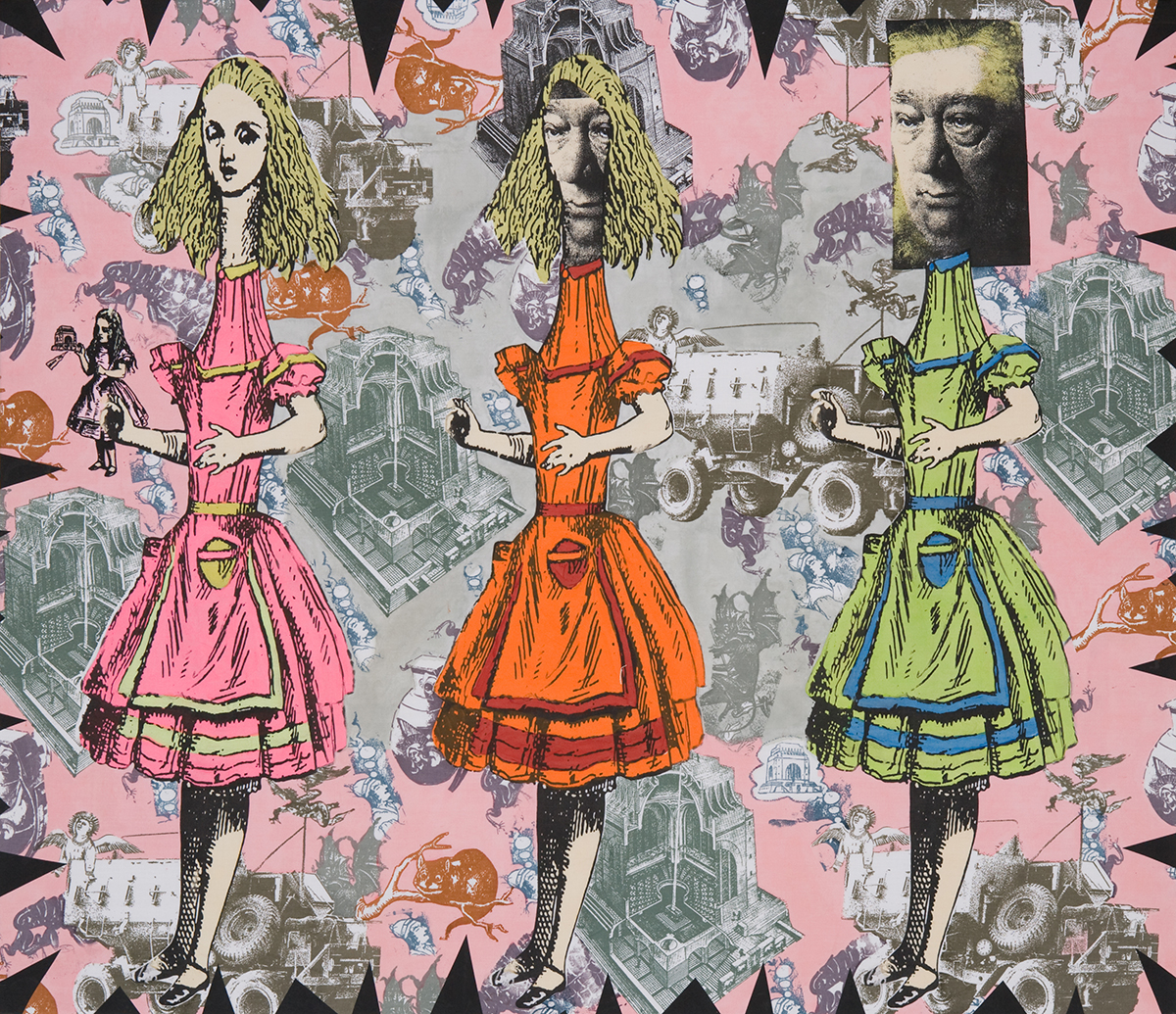

SELF-PORTRAIT IN SHRAPNEL – IVOR POWELL

IVOR POWELL Something that runs through much of your work is a disparateness of reference, the collisions of borrowed imagery. In the old silkscreens from the early 1990s – like the Alice in Pretoria series – images of military hardware and soldiers are forced to live together with strangely distorted Victorian illustrations of an elongated, startled Alice in Wonderland. Grand Guignol B-movie style bounces up against the very recognisably South African social realism of beggars with cardboard placards. Stylised homoeroticism versus photojournalism; sentimentalising flower decoration framing unashamed big dicks. The hallucinatory horror – Alice morphing into Paul Kruger in one of the prints. It’s tempting to see the component images in the register of dream imagery, bound together by the febrile logics of anxiety, loathing and fear, rather than the rational logics of everyday life.

STEVEN COHEN Alice in Pretoria was the first range of textiles I formulated in the army psychiatric hospital in my initial year in the South African Defence Force. I started making them in 1987 while I was in my second year of incarceration in the army. The Alice images are completely accurate to John Tenniel’s original drawings. With most of the objects or images I make use of, the horror is intrinsic to the found object. It needs no distorting, and benefits from as little alteration as possible. When I find an object that scares me, it is because it is already terrible unto itself.

UNTITLED (ALICE IN PRETORIA SERIES) | c1988

HAND-COLOURED SILKSCREEN ON CLOTH 104.5 X 122CM

‘I AM AN ARTIST AND I AM A DOG. I AM A FAGGOT AND I AM A JEW. I AM WHITE AND I AM AN UGLY GIRL. I HAVE A COCK AND I AM SOUTH AFRICAN. I EXPLORE MY LIFE THROUGH ART AND I AM PROUD OF MYSELF. I DON’T CELEBRATE MY QUEER IDENTITY ON ONE SPECIFIC DAY ONLY. I USE EVERY DAY OF MY LIFE TO EXPRESS PRIDE IN MY DEVIANCE.’

STEVEN COHEN

PIECE OF YOU (FAGGOT) 1998 | PHOTO : JOHN HOGG

DIGITAL PRINT ON COTTON PAPER

60 x 35CM

IP What interests me in these ideas is not what is usually brought to the foreground in discussions of ‘The Work of Steven Cohen’ – the obviously provocative and confrontational juxtapositions: pope and penis, postcard-innocent children and monster cocks – the shock horror element. Nor the baitings of the bourgeoisie you do so well – the sparkler up the arse, eating shit as you did in the performance Taste, the appropriation of holy Judaic symbols in the context of what Shaun de Waal rather nicely called ‘monster drag’, the theatre of cruelty aspect to your work.

What I’m concerned with is something more innocent perhaps but, at the end of the day, more explosive. It’s the deferred patterning or presentation of self in your work. The position from which you make your art is multiple and fragmented – and essentially unresolved. You come to your art as Jew, as fag, as democrat, as drag queen, as tortured white South African, as compassionate and morally driven human being, et cetera, et cetera. Each of these elements comes from or signals one of the worlds you inhabit, one of the elements that make you up. Everything does have its reference and its interconnection, but at the end of the day the real interconnection is signally idiosyncratic: the bonding principle that it all reflects (usually in a sulphurous mirror) is nothing more or less or other than your Self with a capital S.

But that Self comes into being precisely in the making of the art – in the space you open up between real-time and the time of art and reflection. It’s something I see as being equally important in the plastic artwork and in the performances, this holding-in-tension of highly charged but unresolved elements. Everything in this way becomes a kind of deferred self-portrait in fragments – maybe shrapnel, some kind of fallout from the process that is Steven Cohen.

INSCRIBED IN THE BOOK OF LIFE

IP The Inscribed in the Book of Life installation is, I think, the clearest and most explicit example in your work of the identity constituted in fragments.

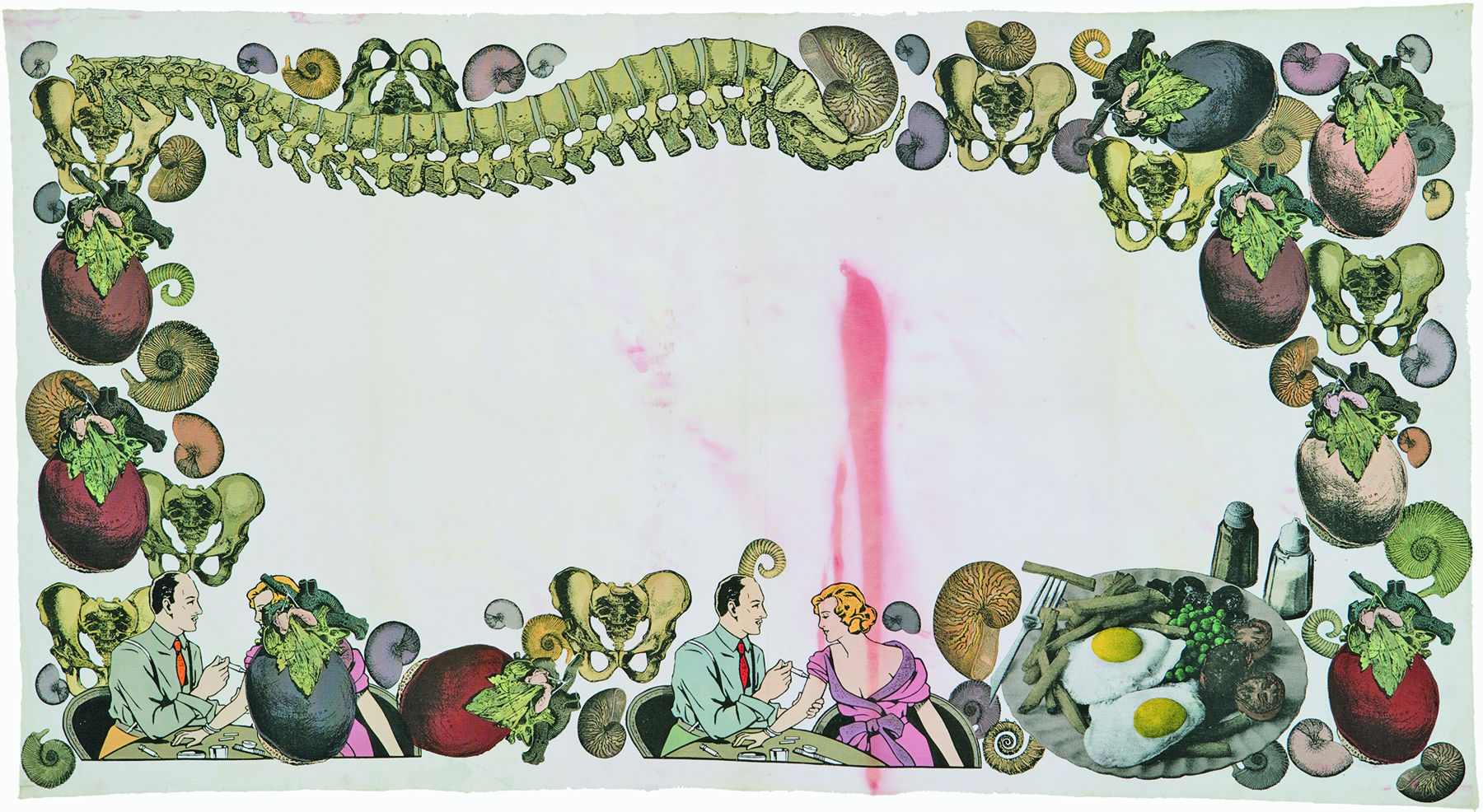

Note: An ongoing project, Inscribed in the Book of Life is presented in the Life Is Shot, Art Is Long exhibition on two contiguous display tables. One has genuine Nazi-era identity documents – the Deutsches Reich Arbeitsbuch, Reisepass, Wehrpass and Soldbuch (the books of work, travel, military service) – resonant with the horror of their history and with official stamps, stickers and identity photographs. The pages have however been idiosyncratically modified to Cohen’s artistic ends, with the addition of family photographs, occasionally annotated, of forebears caught up in the Nazi atrocities; of sentimental Victorian decorative floral, avian and fairground elements such as those used in scrapbooks characteristically made by girls; pompous period photographs; Reich-vintage Stars of David superscribed with the legend ‘Juden’ … These are punctuated with the occasional jolting obscenity: a postcard in which a puckered vagina and anus have been airbrushed into the image of a face; an Indian boy with monstrous elephantiasis of the genitalia; images of torture and inhumanity.

E-mail note to IP from Sophie Perryer: Inscribed in the Book of Life refers to the table of 30 books; the other table is research material, which Steven will continue to use in making more collaged books … In some places you’ll see he has written next to photos – for example, ‘the day Bobba arrived in SA’ or ‘Bobba Ray and the KGB’ – according to Steven: ‘Bobba (Yiddish for grandma) Ray and the KGB (genuine KGB archival photo) because she was Russian born and Russian speaking until her death. Other family members are Zayda (grandpa Sam), my uncle Hymie Katz whose nickname was Dogz, Aunty Ronza, various family members who disappeared during the Holocaust …’

SC Collecting Nazi memorabilia is forbidden by law in many European countries – which just makes it more circuitous, strange, exciting … and necessary. The illicit adventures of finding it, paying for it and crossing borders with the contraband, not to mention the strange milieu of those in the trade of it – it’s all a bit like being in the resistance in a Boy’s Own adventure. But then, whenever I find something authentic I am quietened by the reality of it and the belief I have in the project, convinced again, re-filled with conviction.

IP I guess the reason the authorities try to control access to this stuff is because they fear it will become grist for the ever-grinding mills of neo-Nazi and other fascist urges in the European collective consciousness. (A less generous view might focus on a kind of latter-day damage control by theGermans on one side and the paranoia of the international Zionist lobby on the other.) As a Jew, your engagement with such material is, of course, different. What for the average skinhead is a piece of memorabilia becomes, for you, a relic. In both uses though – as relic or as memorabilia – what gives the item its potency is the tracery of its history, the effect of time focused and frozen within the object. Because of everything invested in them, these things become memory made flesh, so to speak.

SC I feel like a Nazi hunter when I find fragments of the Holocaust at flea markets. I feel conflicted negotiating the price of a Nazi party card with a young blond person in Vienna – or Germany, New York, Estonia, Belgium, all over France. I also feel joy in gaining possession of it. And I am overwhelmed with something like terror at the brittle surviving fragments that I find, the immense power of the photographs, letters from Gross-Rosen, or Auschwitz, a young Jew’s diary with two yellow Juif stars and a thousand tiny drawings. The things of ghosts, and although the gone are not forgotten and we hear them, their absence is an unintelligible scream, not an explanation. The facts are scrabbled in these shards of paper …

In another way it explains to me a story of birth and survival, of how I managed to be born South African. And every time I find a single object (I now have a collection of hundreds) it is like finding a human tooth in the soil, a remain that alerts me to an absence.

GOLGOTHA

Note: Golgotha is the place of Christ’s crucifixion.

In Cohen’s performance of that name, the Stations of the Cross – the road to Golgotha – proceed from New York City’s Wall Street, hub of global economic imperialism, to Ground Zero (the site of the bombed World Trade Centre). Cohen wears a stockbroker’s suit, and his progress is bedevilled by the fact that he is wearing high, high stiletto heels whose bases are a pair of human skulls.

SC I call them skullettoes – a combination of skulls and stilettos. Golgotha is a work made on feelings rather than convictions. It started off all morally indignant when I found the human skulls for sale, but over the years making the work it became about trauma and loss and grieving rituals and how to stay human. In New York it is possible to do what you can’t do in the Congo or in South Africa: to buy skulls in a shop in Soho. Paying $2 000. Getting a receipt – which includes tax to the American government. In the piece I am walking on dead Asian people – freshly dead, never buried, with all their teeth, no dental work …

IP They’re definitely Asian?

SC Yes, there’s a particular formation of the bone at the bottom of the skull that is distinctively Asian. I looked in a book of phrenology. It sounds flaky referring to a pseudoscience, but it was in an old edition and the drawings looked realistic-ish. Also I bought a pair of replica skulls in plastic for working purposes and those categorised as Asian best matched the authentic ones. You can buy Asian or African heads. You can’t buy Europeans, certainly not Americans. Conceptually it’s extremely strong to buy human skulls over the counter in a chic shop in an upmarket district in sophisticated New York City, but the actual objects, the shoes, the skullettoes that I fabricated from the skulls, are beautiful sculptural objects – astonishing … strong …

IP How does it feel to be walking, cushioning your tread, on somebody’s skull?

SC It feels wrong. It feels like I know I’m doing something wrong … but I know the reasons I’m doing it are not wrong. The practice of walking on the dead is extremely traumatising for me. I mean, buying them was difficult and even touching them is difficult, because … agh, they don’t feel like nothing. They have an amazing kind of energy that resonates out of them. Maybe that’s me and the culture I come from, because Jews are not big on the dead. There’s this enormous distance between us and death – you don’t see the dead, there’s no open burial, there’s a special ‘wagter’ who looks after the dead, so as soon as somebody’s died they’re not part of the family any more, they’re part of the great system of Judaism … I do feel monstrous walking on the heads of the dead, but sacred in that I know exactly why I am doing it. And insist I will, the true horror of the work is not that I walk in the skull shoes, but that I am able to buy human skulls in a highly regulated and supposedly moral system. The obscenity is something I encounter rather than something I invent. I only go one step further when I develop them into transgressive footwear – I mean, art.

FIRE UP THE ART IN REAL TIME

IP You describe your performance work – or a part of it – as being done in the register of ‘please persecute me’. Flip maybe, but also kind of true. In Cleaning Time When you take that giant toothbrush to the cobbles of Vienna remembering the time when the Jews were forced to polish the square with their toothbrushes (I presume the Austrian authorities were going overboard in demonstrating their commitment to the Third Reich), the work only really gets a shape when that dumb cop feels either moved or obliged to intervene.

SC He seems kind of sensitive and naive and unwilling to do what he does; there’s a gentleness to him. He’s not like the vicious old dude who puts him on the case, giving him the instructions to act. You see it clearly in a few seconds of the video. Which is why I found it interesting – he is totally directed by a grumpy older fuck.

IP My point is that, in a way, you require that intervention to round out the narrative of the piece. The point at which the victimhood you are exploring, that is your subject, is enacted in the real-time scenario of the performance – that is where the black humour is released. The cop in a way becomes the straight man, in the same way that the guards at the Centre for the History of the Resistance and Deportation in Lyon reacted to you in drag and Mogan David.

SC That was the Police Nationale who were there at the behest of the director of the museum, denouncing degenerate art. They took us in for most of a day, handcuffed and photographed and all me front, left, right, face and crotch.

IP OK, but they also got trapped into the dramatis personae?

SC Even when people don’t overtly react or overreact, that still gets written into the script.

VOTING, 1999

PHOTO: JOHN HODGKISS

CLEANING TIME, VIENNA, 2007

PHOTO: MARIANNE GREBER

‘I’M NOT THE KIND OF PERSON WHO BEHAVES LIKE I DO’

STEVEN COHEN

IP In a note you made responding to some of my blunderings, you said: ‘I’m not the kind of person who behaves like I do’. I think this is true, and I think it says a lot about your practice as an artist, particularly your performance work. The things you do, the ways you behave in the cause of art: you stick lighted sparklers up your arse at award ceremonies; decked out in parodistic heels and chandelier costume, you interact with squatters being forcibly removed; ceremonially you drink anal emissions, toasting your (presumably speechless) audience with the traditional Jewish ‘l’chaim’ (‘to life’); you haul yourself in gemsbok-horn heels to vote in the general elections; you attend right- wing gatherings in caricature drag; in a recent performance on the roof of a national dance centre you masturbated in public …

Characteristically, you go over the top. And good for you: it’s funny, it’s fantastical, it makes for wonderful, often gobsmacking theatre. It forces your audience to engage with their own kneejerk viewpoints and prejudices, and all those obvious things. It is also highly extrovert. In the way it imposes itself in real time, it stands in something like the same relation to most performance art as extreme sports do to cricket.

Real-time difficulty and discomfort … In your performance at the Life Is Shot opening, you couldn’t walk in the shoes you were wearing, you literally couldn’t move around unassisted. People helped you for a bit, but then they settled into drinking and discoursing. Eventually you just ended up in a kind of heap on the floor.

SC For me it’s not about looking for the limit and staying just within that, it’s about looking for the limit and going just a little further from that. It’s not like jumping off the cliff and then hanging on by my fingernails; it’s about allowing myself to fall and in that moment of falling accepting the enormous realisations that come … because I’ve had friends that have committed suicide jumping off buildings with their jersey pulled over their head. I think in the moment of falling you see a lot. For me that’s a kind of metaphor I carry with me. It’s like blinding myself in order to be able to see.

The Life is Shot performance was also an experiment in depending on other people. My performances are like forced interactions between us (artist and audience) – not usually on the level of touching each other, it’s more through the visual – but here it was literally a case of ‘I cannot do it unless you help me’ and then I reached a point of ‘I can’t do it even if you help me’. I don’t know what validity it has for people, but you know it’s also ridiculous in the context of a simple social event like an art opening – this isn’t a major work at a biennale with people watching – and I think that’s a good place to put

on performance art, in the midst of a tea party, or on a boring Tuesday afternoon. I’ve always looked for a non-theatrical time or setting for an enormous action.

IP I’m interested in the way you describe it. In the classic performance situation the artist does the performance and the audience watches it. The way you talk, you are as much the audience for your piece as the performer of it.

SC The normal thing is the audience is completely passive and the performer completely active, but in these interactions I tend to adopt a certain passivity of letting things happen, of being very quiet, of being outside myself and observing myself … Not kooky, spooky astral-travelling shit, but in the sense that when something really enormous happens you do feel you’re outside yourself. As Andy Warhol said, when real life happens to you, you feel like you’re watching TV. Like when you break your arm … I’ve got memories of watching it happen, of seeing it from the outside. It’s also about activating the public, forcing them to be active, even if it’s in a refusal to watch or to leave, even if it’s to touch me or hit me or call the police. It’s about leaving all that open.

ENORMITIES

IP Is it important to you that you’re not the same at the end of a performance as you were at the beginning? I’m thinking of the really difficult ones – Chandelier would be a good example, there’s something really painful about the piece, just watching it. I’m interested in the language of that pain and the way it’s projected … the way you engage with extremity and how that engagement becomes the subject of the work.

SC That’s very much what I’m looking for, what you’re describing – that engagement with all of those elements of danger, the unknown, infinite possibility, failure … Blood and death are not what I hope for, but they are elements I must accommodate. If someone’s coming to hit me, I don’t know kung fu or anything, I just have to accept what is going to happen.

I feel very different after a performance. I don’t feel better or stronger; I don’t feel as though I know something I didn’t know before. I just feel altered. So it’s not about improving myself, it’s not a form of therapy, or people talk about it as catharsis. I don’t think it’s any of that. It’s the kind of shit that happens to you when you have a really woes day … By the end of the day, you’re not the same, a lot of stuff has happened. I’ve written about it and I said something about feeling injured and cleansed.

But now these days I feel polluted, not cleansed. I feel a bit damaged … more and more … which is why I’m finding it difficult to keep making performances. Also I’m getting older, I’m 47 years old, nearly 50. The work I’ve done makes me feel 75 … my body and my mind … I mean Chandelier’s hard on the body, but it’s even harder on the mind. You watch people with nothing losing what they don’t have … and I feel white and weird and I feel voyeuristic and I feel I don’t have the right to be there and at the same time I have to maintain a belief in the project which gives me the right to be there. I believe in the art that I’m making more than I believe in myself, because I know that I’m often not right.

IP You, Steven Cohen, are there of course. But you’re also masked in a way. Tell me about the persona or personas you adopt for your performances.

SC I like to say it’s not a persona, it’s part of me, but you know … you’re right, it’s a persona. It gives me the liberty to reveal myself because I’m so well disguised, behind the make-up, behind the shoes and the stockings and the bizarre costumes … It’s a head-to-toe mask and from behind there I can say things I really believe in.

IP There is a sense in which your performance work scrambles the philosophical order of things. The way I see it, you pursue metaphor in extremity, and extremity in metaphor. Where the two intermesh is the zone of what you are in the habit of calling the ‘enormous’ experience. In this way, the language of your art-making subsists in psychopathology and cultural pathology. Its syntax is fetish. But what interests me particularly is the fact that all of this extremity … enormity … whatever you want to call it, is yoked, as I see it, into the service of what is essentially a moral vision, a vision that is humanist, shot through with the pathos of life and informed by powerfully felt values.

From my side, I want to end with two big thoughts, big but I think not insupportably so. One is that in your artistic persona – I note here particularly that your career was hatched in a psychiatric ward during your military service – you take on at least some of the characteristics of the shaman. At least in metaphor, your practice of going that little bit further than the edge is not far from the courting of the near-death experience that characterises the shaman in society. At the same time, the particular species of truth that you seek out – that detached quality you talk about, being there and watching at the same time, not being the same at the end as you were at the beginning – these things are not far from the particular truths brought back by the shaman from the ‘other side’. I don’t know to what extent I am talking about metaphor and to what extent it is experiential, but it certainly occupies some point on the continuum between the two; you would not be feeling so existentially exhausted otherwise.

The second – and this is not unrelated – is that, in your persona, in what you called your ‘please persecute me’ approach, you set yourself up as a kind of sacrificial victim, in metaphor at least offering yourself in suffering to wash away the sins of the world. Funny stratum of metaphor for a nice Jewish boy to be mining …

SC in email note to Sophie Perryer: The end of Ivor’s text is so consistent with the birth of the performance artist in me which also took place in a hospital, those months in Rietfontein Fever Hospital 10 years after the boshouse. I’ve written extensively about the effect of the disease on even the colours of my body – the yellow eyes, the black piss … how that made me aware of the palette of possibilities that my body offered. Asked who or what inspired me in the past, I’ve even mentioned this microscopic virus that tried to kill me.

STEVEN COHEN COMPANY

24 rue Succursale | 33000 Bordeaux | France

Samuel Mateu

Administrateur de production | +33(0)6.27.72.32.88

production[@]steven-cohen.com